Find out what drives parental burnout and explore effective tools to support both your mental and physical health in this article by the American Psychological Association.

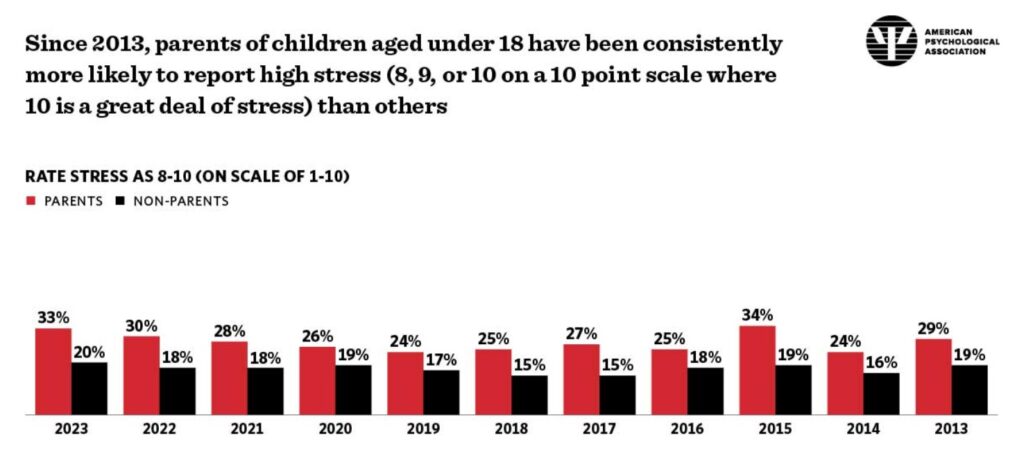

Parenting can be incredibly rewarding, yet can also bring a range of challenges and demands, from sleepless nights and toddler tantrums to navigating the teen years, not to mention financial and relationship strains. In fact, an analysis of 10 years of APA Stress in America data showed that parents of children under 18 are consistently more likely to report high levels of stress than others. And in 2023, one-third of parents rated their stress as high (8, 9, or 10 on a 10-point scale where 10 is a great deal of stress) compared with just 20% of the rest of the population.

Sometimes stress can lead to burnout. Burnout, a syndrome characterized by “emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decrease in self-fulfillment,” is a result of chronic exposure to emotionally draining environments (Rionda, I. S., et al., International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 18, No. 9, 2021).

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized burnout syndrome in its International Classification of Diseases as an occupational condition linked to several health symptoms, such as fatigue, changing sleep habits, and substance use and characterized by energy depletion, mental distance, or cynicism related to one’s job and reduced efficacy. While WHO references this specifically in the occupational context, for many, parenting is a primary occupation and for all parents, the role comes with significant expectations and demands, much like paid occupations.

What advice do psychologists have to offer on how parents can manage stress and burnout?

Talk about it

Open sharing about feelings of burnout can facilitate social support, a much-needed resource for stressed-out parents short on coping skills. But admitting you’re struggling isn’t always easy; burned-out parents often feel isolated and ashamed, which can prevent them from healthy dialogue with supportive people.

Data suggest parental burnout is a lot more common than most parents think: According to the IIPB Consortium study, up to 5 million U.S. parents experience it each year. The first step, Moïra Mikolajczak, PhD, a professor of psychology at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium said, is understanding you’re not the only one snapping at your kids or camping them in front of the TV all day. Talking about parental burnout and stress openly can further normalize the experience, she said, removing some of the shame.

Robyn Koslowitz, PhD, a clinical psychologist and director of the Center for Psychological Growth of New Jersey recommends finding other parents experiencing similar feelings.

Because shame only compounds burnout feelings, the key is to share your experiences in a nonjudgmental atmosphere. While the internet can facilitate such connections, Koslowitz cautions against relying on social media for validation. Instead, seek out virtual communities where rules about shaming are enforced, such as moderated social media groups or message boards.

If your stress is impairing your functioning or causing suicidal ideation, it’s important to reach out to a mental health provider for professional support.

Change your vantage point on parenting

If you’re feeling exhausted by your parenting role, reappraise your perspective. Look for opportunities to grow or areas of your life you’re grateful for. It may help to reframe the difficulty as a challenge—something you can overcome—rather than as a threat that positions you as a powerless victim (Drach-Zahavy, A., & Erez, M., Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 88, No. 2, 2002).

Reappraisal won’t expunge the difficult circumstances from your life, but the change in perspective might help you identify new strategies to tackle challenges or a resource to help you cope. If all else fails, acknowledge that the challenge is likely temporary. Children grow and change, presenting parents with new joys and new challenges that might be better suited to your parenting strengths.

Make small changes

Parental burnout can hit particularly hard because, unlike occupational burnout, it’s not always possible to take a vacation—which may leave you feeling like you can’t escape the stressor. When your stress level outweighs your resources, Mikolajczak suggests finding smaller ways to lower stress levels.

“We tend to see one or two big factors as responsible for stress—perhaps your son is difficult and your husband is never home, which you can’t change,” she said. “But one has to remember there are many stressors tipping the scale.”

Rather than fixating on the big stressors, Mikolajczak advises rebalancing the changeable ones that contribute to your feelings of exhaustion over time. For example, if your chore list exhausts you, offload a few jobs to a partner or kids or try to modify expectations regarding timing or quality of those chores. If a child’s constant activities are a burden, cut down on commitments or schedule carpools with other parents. The key, Mikolajczak said, is to be flexible and balanced.

Parents can also look for ways to expand their resources. APA deputy chief for professional practice Lynn Bufka, PhD, recommends that if you have the money, it can be well worth hiring someone to take on tasks that just aren’t getting done or to give yourself a break with a few hours of childcare. “If you don’t have the financial resources, do you have trusted family or friends who might be willing to lend a hand or would welcome an opportunity to be a positive adult in your children’s lives?” said Bufka. Some parents even have success forming agreements with other parents for everything from watching one another’s children to cooking in double batches and providing each other a meal. “Get creative with your network,” advises Bufka.

Grow your parenting skills

Parents should consider adding skills to their parenting toolboxes, according to Lisa Coyne, PhD, a senior clinical consultant at McLean Hospital OCD Institute in Massachusetts and an assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School. “Because burnout is marked by a disconnect in how you’re parenting now and who you were before, growing in their parenting skills can give parents a sense of efficacy in decreasing parenting-related stressors and, as a result, mitigate feelings of burnout,” she said.

Isabelle Roskam, PhD, a professor of psychology at the Catholic University of Louvain, said that while reading books about parenting can increase feelings of failure and shame for many, other resources can provide a much-needed confidence boost in parenting by providing targeted skills. Look into local seminars, ask about mental health and parenting resources at your child’s school, or find a therapist who uses evidence-based behavioral training programs for parenting.

Stop saying “should”

Research suggests parents who are perfectionists and those who put pressure on themselves experience higher rates of burnout (Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K., Journal of Child and Family Studies, Vol. 29, 2020). Finding practical ways to relieve that pressure can reduce burnout risk.

“Sometimes our demands are top-heavy because we have particular expectations about how things should be done—how well we should be doing things and how happy we should be doing them,” said Natalie Dattilo, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an instructor at Harvard Medical School. “These unrealistic expectations increase our load, and they are some of the first things we can take off the plate,” she said.

Dattilo commonly recommends her patients avoid “should” statements, which she says add shame. For example, if you’re overwhelmed and tell yourself you “should” spend more time playing with your kids, you’ll only feel badly when you don’t measure up. Try swapping your “should” statement with “It would be great if I had more energy to play with my kids.”

“That reframing can help parents deal with their current reality rather than what they think they should be doing, so they can deal with their circumstances the best they can with the resources they already have,” Dattilo said.

Take microbreaks

Self-care is a vital component of recovering from any type of stress, but it’s not necessarily realistic for everyone to plan a kid-free getaway to recover.

But even tiny breaks can help—for example, locking the door in the bathroom for 5 minutes to take deep breaths or sitting in your car to listen to a guided meditation after grocery shopping can enhance resilience in parenting. “Rather than a whole weekend of vacation or even an hour, focus on finding opportunities for relaxation and pleasure in ways that are manageable for you,” Inger Burnett-Zeigler, PhD, an associate professor of psychology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine said.

Self-compassion can add another resource to help you manage stress, according to Burnett-Zeigler. When you take breaks, try to find small ways to recalibrate your thinking. Acknowledge the pressure you may put on yourself for how you should be doing or feeling and remind yourself that you’re doing the best you can with the resources you have.

Find meaning

When you feel detached from something you care about, Debbie Sorensen, PhD, a Denver-based clinical psychologist, said it can be helpful to reconnect with your values and reorient yourself to the meaningful aspects of parenting. “We can really get lost in the drudgery, and it takes work to carve out special moments with your kids that remind you parenting can be fulfilling,” she said.

Even if it feels overwhelming, practice behavioral activation by planning a small, low-stakes activity—a trip to the park or watching a favorite movie—to do with your kids. Remind yourself in the experience or debrief after about your kids’ positive qualities, as well as the skills and qualities you bring to the table as a parent. Remembering the meaning you’ve felt in the past as a parent can provide a resource when exhaustion and resentment return.

Parenting, like any realm of life, can be both difficult and rewarding at the same time. “Some of these feelings of resentment, shame, or guilt for parents come up because we live in a society that says we should love our kids unconditionally, and if we’re frustrated, we’re bad parents,” said Riana Elyse Anderson, PhD, an assistant professor of health behavior and health education at the University of Michigan. “But that you love your child and acknowledge parenting as a very difficult thing can be true at the same time.”

Check out the original article and full infographic here.